The

Israeli citizenry is one large voting body – dividing the country into

electoral districts would have been unacceptable symbolically. Two separate votes are cast, for a prime

minister and a party.

A

party gets its proportional share of seats in the Knesset, with the restriction

that it needs 1.5% of the total vote to get any seats at all. This seems to be the lowest threshold of any

national proportional representation system -- a number are analysed by Gary

Cox, Making Votes Count : Strategic Coordination in the World's Electoral

Systems,1997. The Knesset has 120

seats, so the threshold rule means that every party receives at least two, and

it means a party needs about 25,000 votes.

Parties

put up “lists” of candidates – series of individuals who will take the seats

the party wins in the order they appear on the list. Parties can make pre-election public deals where “excess” votes

from one (those that add no seats) are assigned to another. This is another clue of who is near who in

political space.

Barring

unusual circumstances, an election is held every four years, but the Knesset or

prime minister can hold early elections -- Netanyahu was in power only 2 ½

years when he called for further elections hoping to increase his Knesset

support.

Before

1992, the prime minister was chosen by the president asking some MK (member of

the Knesset), typically the head of the largest party, to form a

government. The new system with the

direct election of the prime minister along proportional representation is a

hybrid that seems to be unique in the world.

To

stand for prime minister, one must by the head of a registered party and be

nominated by a party or group of parties with at least 10 seats in the outgoing

Knesset, or by a popular petition with 50,000 voters’ signatures. The prime minister needs 50% of the vote,

and if no one achieves this in the first round, the top two contestants hold a

runoff two weeks later. The winner has

45 days to form a government, for fear of another special election for that

office. A simple majority of the

Knesset can vote no-confidence and hold a new election.

The

purpose of the change was to increase the prime minister’s strength vis-a-vis

the small parties, who would extract promises in exchange for their support in

forming a government, and vote no-confidence otherwise. However, the promoters of the idea seemed to

have forgotten that voters are strategic thinkers. The system has caused a proliferation of small parties both

standing for election and entering the Knesset. Voters had previously felt constrained to vote for the party of

their favored PM candidate, but now are freer to vote for whichever party

endorses their favorite special issue.

In the 1999 election 33 parties ran, and 15 were elected.

Until

the last days of the 1999 campaign, a second election seemed like a

possibility, which might have been followed by a third election if no

government could be formed. After a

long election process (180 days) these prospects were dreaded by just about

everyone in Israel except a collector of election posters. There is considerable support for returning

to the old system.

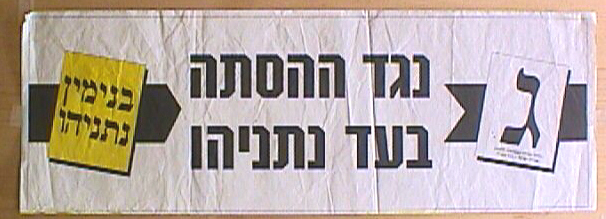

Below

are sample posters showing the two votes cast.

Netanyahu’s party calls for a white ballot for itself and a yellow one

for him as its leader, but the religious United Torah Judaism party also

supports Netanyahu for prime minister, although he is not the head of their

party.

The

list of 33 parties running, with the Hebrew letters representing each one, is

shown further below. Most of them are

one-issue parties, standing for Romanian immigrants, the legalization of

marijuana, the rights of pensioners or the promotion of casinos in Israel. The

Natural Law Party came in sixth from the bottom. Fifteen of them achieved seats.

|

|

|

|