|

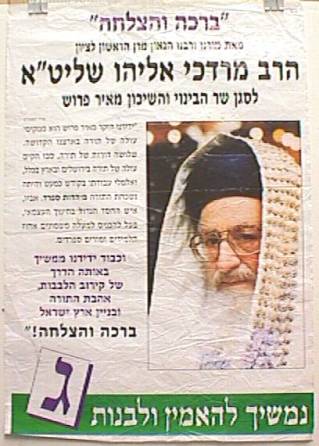

Jewish

religious groups in Israel have a complicated history and structure. Eliezer

Segal's webpage at the University of Calgary gives an outline. The

religiously-oriented parties that won seats in May 1999 were: n

Shas, representing Sephardic jewry (431,000 votes, 17 seats), whose

posters have their own webpage here, n

United Torah Judaism (126,000 votes, 5 seats) representing the

strictly religious Ashkenazi, or European, jewry, and n

the National Religious Party (140,000 votes, 5 seats) for the less

strictly orthodox. Many

of their posters are influenced by the tradition of pashkevilim, the

printed notices that have been put up in public places of the orthodox

communities, for many decades or perhaps for centuries. These are a major way that the community

stay in mutual contact, given that television and sometimes radio are

banned. They give moral advice,

notify the community of a death, condemn errant members, or most recently

they deal in politics. The combination of a highly literate community and the proscription of electronic media seems rare in the world today. The pashkevilim record the history of religious districts but they seem to have been unstudied. I could find no books on them, and no indication that anyone is saving them. First are some examples of the non-political variety. |

|

|

Don’t

bring computers into your house. If

you must use them, leave them in the workplace. They carry demonic games, and new inventions even allow them to

transmit television. Several rabbis

sign it. |

|

|

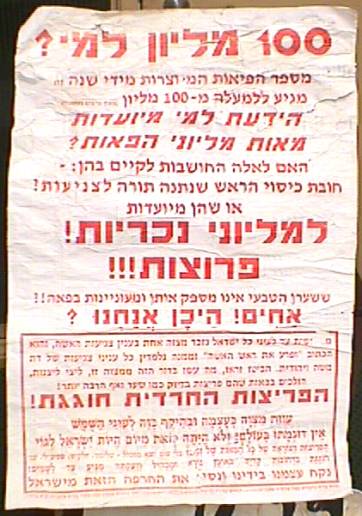

The walls are open to anyone in principle,

although the community will notice who is putting the posters up and may

respond accordingly. Here some

individual or group declares that 100 million wigs are made yearly in Israel,

and who must be wearing them? Non-jews

and prostitutes!! It’s not clear what

the remedy is. |

|

|

A

last example of a non-political pashkevil.

On the right is [will be] a poster that goes up recurrently. A long list of rabbinic leaders, including

many who are now dead, urge the reader to acquire a well-known book against

gossip, the evil tongue. |

|

|

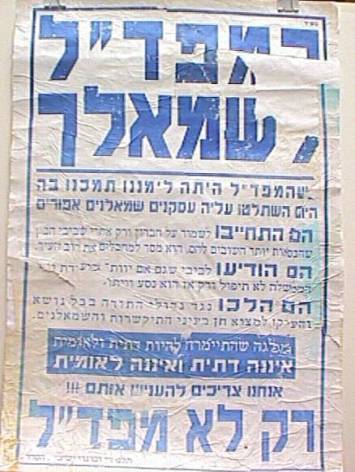

Like

the pashkevilim, many of the religious posters are wordy, with more than a

single slogan. They are not meant to

be glanced at from a passing car. Here

a group of rabbinic students berates the more moderate National Religious

Party, or Mafdal, for its support of Netanyahu’s peace process. The NRP claims to be “at your right”

meaning supporting you, but it is really “at your left,” taken over by gray

leftist activists. “Only not Mafdal,”

it says, varying a catchphrase discussed on my Netanyahu page. Other

examples of wordy postures are on the Shas page. |

|||

|

|

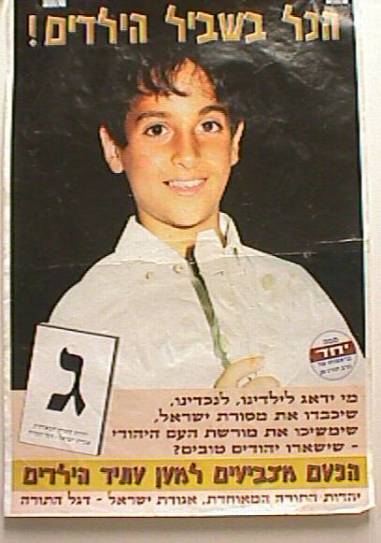

The

United Torah Judaism party argues for the protection of the children’s religious

upbringing. The young boy holds a

recorder, or challil, which perhaps symbolizes the innocent enjoyment

of Jewish culture. |

|||

|

|

|

|||

|

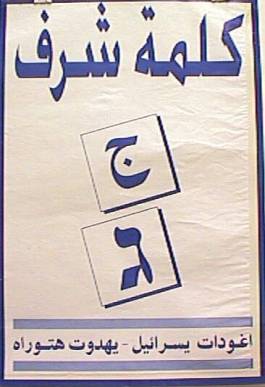

Here

two religious parties, the UTJ, with its ballot letter gimmel, and the NRP,

letter bet, claim the support of the same Sephardic rabbi. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

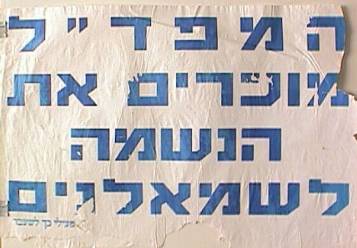

The National Religious

Party’s slogan: putting the soul in Israel. |

||||

|

|

A

play on the slogan: Mafdal has sold its soul to the left. Israel’s

election laws forbid parties that endorse violence or reject democracy or the

existence of the state of Israel.

Meir Kahane’s group was accordingly banned, but his supporters in the

group Kof put up this anti-NRP poster. |

|||

|

|

The

NRP suffered a split before the 1999 elections, with several important

members, notably Bennie Begin, son of the former prime minister, forming

their own party, the National Unity Party.

The new group was more hawkish and had weaker religious

credentials. This poster, my favorite

of all the ones I collected, says, “The woven yarmulka has only one

head.” The colorful woven yarmulka,

as opposed to the black leather or cloth model, symbolizes moderately

orthodox jewry. The poster is calling

for unity under their leadership. |

|||

|

|

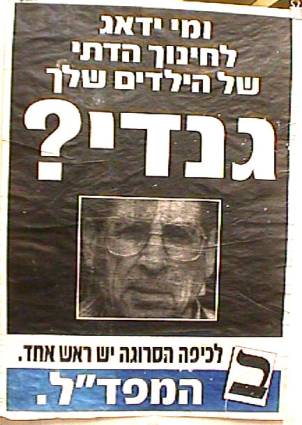

Here

the message is put less gracefully, as an explicit attack. Showing a sinister picture of one of the

defectors, it asks: “Who will care for the religious education of your

children, Gandy?” |

|||

|

|

The

most liberal religious party is Meimad, and it joined with Barak’s One

Israel. The symbolism is young people

pulling together. Some have yarmulkes

(set jauntily to the side, not the way the ultraorthodox would wear them),

some are bareheaded, one is female. |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

“ultraorthodox” UTJ’s ballot letter appeared on many railings and

windows. Like Shas’s posters it

stayed up long after the election, supporters using it as a way to say who

they are. In a TV ad the letter was

animated and bowed down in devotion. |

|||

|

|

Meretz,

a party promoting secularity, ran under the slogan “To be free in our

land.” The line is taken from the

national anthem, and in Meretz’ use has the connotation of free from the rule

of religion. The UTJ adapted it: “To

be a believing Jew in our land.” |

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

|

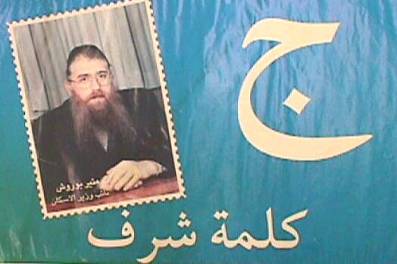

Members

from the UTJ do not accept cabinet positions, in order to stay untainted by

the secular actions of the government.

However Meir Porush, its leader, had held the post of Deputy Minister

for housing under Netanyahu. Both the

ultraorthodox jews and Israel’s Arabs tend to have large families and so have

a special interest in housing policy.

He made an appeal to Arab voters, with the slogan, “Word of

honour.” The symbolism of the postage

stamp is unclear, perhaps a suggestion his governmental position on internal

matters. |