On Easter Sunday, April 5, 1772 a three ship expeditionary fleet sponsored by the Dutch West India Company arrived off the coast of an unknown island. It’s captain, Jacob Roggeveen found approximately 2000 – 3000 inhabitants on what he and later European explorers characterized as a sparsely cultivated land mass studded with hundreds of stone statues. Though interesting from an anthropological point of view, the island held little commercial or strategic value for the Europeans and explorers generally dismissed it as a barren speck in the Southeastern Pacific; perhaps even an environment waiting to develop. What they didn’t know was that the desolation was the end result of what many consider to be one of the most extreme examples of complete ecological collapse in the world.

The environmental wasteland that Roggeveen and his crew encountered was an image inconsistent to its former self. Produced by the fusion of lava flows from three intersecting submarine volcanoes along the Nazca Tectonic Plate, the 166 km2 fragment of land is characterized geologically by not only the abundance of basalts and andesitic rock, but fertile soils as well.

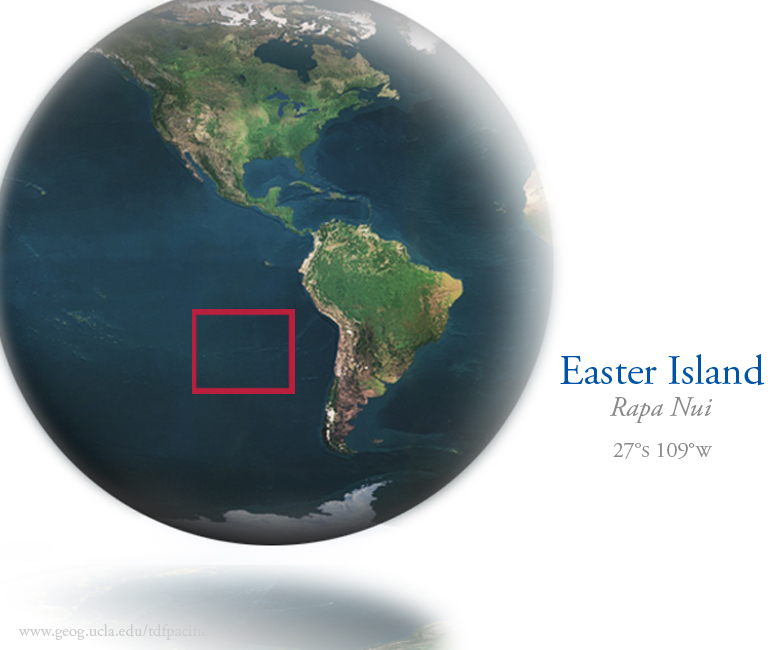

Though politically associated with continental Chile, Easter Island is positioned more than 3,700km west of its affiliated coastline and more than 2,200 km east of Pitcairn, the nearest inhabitable island. This geographical separation has prescribed a climactic condition for Easter Island unreflective of its host country. Subtropical by classification, it is characteristic of the island to present a moderate climate and an annual rainfall average of 1,250 mm. While southeast trade winds yield a particularly windy winter season from June to August, the island surface temperature fails to drop below 14°C. As December approaches, elevated levels of humidity accompany subtly rising temperatures. As the summer season continues through February, it is common to experience temperatures approximating 24°C. Such moderate climactic temperatures are maintained even through the months May to June when the island experiences its heaviest rainfall.

Speculative models derived from the combination of archeological and paleontological studies have described a vegetative-rich land cover unlike anything the island has exhibited in the last 500 years. While prehistoric alterations in the island’s topography can be explained by repeated climate changes and volcanic activity within the last 38,000 years, Easter Island’s most critical and instantaneous degradation has only recently begun to be explained.

Presumably influenced by their seclusion within the Southern Pacific waters, records indicate that the natives once referred to their island as te pito o te henua, often translated as “the navel of the world” or more aptly, “the center of the world.” Although their motives have yet to be determined, anthropological and cultural cues have confirmed Polynesian immigration to Easter Island. Regardless of reason, the Polynesian settlers inhabited the island and brought with them the cultural beliefs that eventually evolved, leading to the production of Easter Island’s most iconic figures; the stone moai. Built to honor their ancestors, the 14-ton colossal statues were carved from the abundant basalt and transported miles to be positioned along the periphery of the island. As speculations have it, this practice continued until a lack of floral resources halted the moai production and left many partially completed stone figures abruptly abandoned. As resources dwindled, Easter Island stepped closer and closer to becoming the barren grassland seen by Roggeveen and every visitor thereafter.

Many who have studied the island have illustrated a culture that thrived for hundreds of years and at one point, reached a population of several thousand. Such models are supported by the notion of fertile soils and the presence of fresh water within crater lakes. Some have added that a population of such size would accommodate the exhaustive construction and movement of the moai without sacrificing necessities like the production of food. This theory concludes by modeling the final exploitation of island resources and the inevitable warfare prompted as a result of starvation. While such theories account for the island native’s demise by focusing on the civilization’s misuse of resources, others such as archeologists Terry Hunt and Carl Lipo have argued an alternative model. After radiocarbon dating samples from Anakena, one of the islands only sandy beaches, they constructed a new timeline placing the arrival of the Polynesians four centuries later (1200AD) than traditional findings (800AD). This would imply that events such as complete island deforestation occurred too abruptly, suggesting that other factors were involved in the destruction of their resources.

While no written language was left to illustrate a more accurate history, the mysteries of Easter Island’s past are continually debated over. Regardless of concern, whether it be archeological, anthropological, geological or geographic, all forms of research have both uncovered and relied on floristic and faunal records. It is with the culmination of all these records that we begin to understand how the island we know now, has become so barren.

A CHANGING LANDSCAPE

The floral composition of Easter Island has changed dramatically over the past several hundred years. When European explorers first arrived on Rapa Nui in the late 1700’s, they discovered a grassy vegetative matrix devoid of plants greater than 3m in height. In fact, Gonzalez went so far as a exclaim that “not a single tree is to be found capable of furnishing a plank so much as six inches in width” in 1770 and Roggeveen remarked in 1772, that the island was “destitute of large trees.” But this wasn’t always the case. Though whittled down to small woody shrubs, grasses and ferns by the late eighteenth century, the island did, at one time, support an environment entirely different from that observed in the present day.

Around 1984, the geographer John Flenley collected core samples from three volcanic crater lake-beds on Rapa nui. In them, he discovered a fossil pollen record which spanned the past 37,000 years and pointed to the existence of a subtropical forest dominated by large palms. His find was further supported by the research of scholars such as John Dransfield and Terry Hunt. Dransfield identified what is believed to be an extinct species of island palm through endocarps discovered in a cave in 1983. Two decades later, Hunt discovered tubular root molds characteristic of large palms in the clay substrate while working in the Anakena dunes in 2005. Coupled with the established pollen data, these discoveries offered insight into a previously unknown lost landscape and have greatly furthered contemporary understanding of Rapa Nui’s past.

While the source of Rapa Nui’s mass deforestation has yet to be identified, select theories prevail. Gnawing marks left presumably by rodents on endocarps of the once prosperous palm lead some to believe that uncontrollable populations of rats were at fault. Others cite the island’s natural fragility as the cause of the collapse while still others point the finger toward anthropogenic over-exploitation of the available resources. Regardless of its origin, the deforestation devastated the island ecosystem.

The loss of the canopy left the soil below exposed to the elements. Subsequent sheet erosion removed the fertile topsoil many plants depended on, making new growth difficult in the harsh conditions. The deteriorating environment had obvious consequences for the island’s inhabitants. Farmers began to experience lower crop yields and responded by occupying upland plots and stone-mulching the land to preserve the remaining soil structure. A loss of trees with little regrowth dramatically depleted sources of firewood and lumber. Jared Diamond cites this period as a turning point in the island’s social history. Shelters became smaller and were built with less wood, earthen ovens became stone lined for more efficiency, and oral accounts are filled with stories of chronic fighting and statue destruction. To survive, the inhabitants began to exhaust the few remaining sources of fuel, causing almost all of the island’s woody vegetation to disappear. Thus, when the European’s arrived near the end of the eighteenth century, Easter Island was a tattered, barren shadow of its former self.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Today, much of the island’s vegetation is limited to grasses, sedges, and ferns. Of the 47 indigenous species of higher plant, there are only two small trees and two woody shrubs (Diamond 1995). None of the endemic tree species remain on the island. The only surviving member of the island’s endemic tree population is the Tormiro tree (Saphora toromiro) which has been extinct in the wild since 1960. Botanists have managed to sustain small populations of the tree overseas but as of 1988, wild reintroduction efforts have been unsuccessful. Though no conclusions have been made, the high occurrence of invasive species may be hampering such restoration efforts.Introduced Stipa spp., Nasella spp., and Sporobulus indicus cover the grasslands and all compete with the native Cynodon dactilon for space. The bottom of the Rano Rakau crater is filled with invasive Scirpus tautora and Polygonum acuminatum (a medicinal plant). Non-native sweet potatoes, sugarcane, bananas, and bottle gourds along with trees like the Asiatic Paper Mulberry and the hau hau have also established a foothold. The high occurrence of these invasive species in relation to indigenous vegetation have pushed the island’s native plants into small remnant populations throughout the island.

Anthropogenic action is also putting pressure on the landscape. Unregulated grazing, clearing of forests for agriculture, and industrial development are rapidly encroaching upon the remaining 5% of the indigenous habitat. Though the Chilean government established a 68km2 national park in 1935, the islanders have failed to recognize the authority of what they see as a foreign government and ignore park regulations. This, coupled with damage from tourism and archaeological excavations also greatly inhibit restoration operations and present considerable challenges for conservation biologists seeking to repair Rapa Nui.

Bahn, Paul, and J.R. Flenley. Easter Island, Earth Island. New York: Thames and Hudson, London, 1992.

Bahn, Paul, and J.R. Flenley. The Enigmas of Easter Island. New York: Oxford University Press Inc., 1992.

Dangerfield, Whitney. “The Mystery of Easter Island.” Smithsonian (2007).

Diamond, Jared. “Easter Island’s End.” Discover (1995).

Hunt, Terry, and Carl P. Lipo. “Late Colonization of Easter Island.” Science 311 [no.5767](2006): pp.1603-1606.

Hunt, Terry. “Rethinking the Fall of Easter Island.” American Scientist 94 [no.5](2006): p.412.

Spriggs, Matthew, and Atholl Anderson. “Late colonization of East Polynesia.” Antiquity 67 (1993): p.200.

Steadman, David W., P. V. Casanova, and C.Cristino. “Stratigraphy, Chronology, and Cultural Context of an Early Faunal

Assemblage from Easter Island.” Asian Perspectives 33 [no.1] (1994): p.79.Van Tilburg, Jo Anne. Easter Island Statue Project.

<www.sscnet.ucla.edu/ios/eisp/rapanui/rapanui.html>World Wildlife Fund. Easter Island.

<www.worldwildlife.org/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/oc/oc0111_full.html>

Acknowledgments

Funding provided by the UCLA Undergraduate Research Center thanks to the Thomas & Virginia Ehrisman Scholarship.

Thank you to Thomas W. Gillespie for his academic guidance.